Supporting the Needs of Autistic People in Healthcare Settings

By Dr Miriam Kirby

Studies show that Autistic people have a reduced life expectancy and poor physical and mental health outcomes. There are likely many Autistic people accessing mental and physical healthcare services that are not receiving services that best support their individual needs, as well as those who are who have not disclosed, are yet to be formally identified or have been misdiagnosed with other mental health conditions.

At The Kidd Clinic, we are noticing an increased interest from psychologists and other allied health providers seeking training to increase their understanding of Autism, how to support Autistic people in neurodiversity affirming ways and how to make adaptations to service provision (e.g., environmental and treatment based adaptations). We are also learning more from our lived experience community about what it is like to access physical healthcare services and some of the barriers that can occur.

A recent study published in 2023 on barriers to healthcare for Autistic adults by Samuel Arnold and colleagues, the first of its kind in Australia, highlighted that Autistic adults experience more barriers to healthcare than their non-autistic peers. Some of the barriers included:

Fear, anxiety, embarrassment or frustration impacts on initiating contact with healthcare providers

Difficulty following up on care

Difficulty making appointments

Behaviours being misinterpreted by providers or related staff

Communication differences

Difficulties identifying and reporting pain and/or other physical symptoms

Sensory discomfort

Difficult waiting room experiences

Pia Bradshaw, Claire Pickett and colleagues in their 2021 paper outline ways to change health outcomes for Autistic people by increasing practitioners’ understanding of Autistic perspectives and experiences as well as by addressing the known challenges and barriers experienced by patients seeking medical attention. Increasing awareness and acceptance of Autism may also help medical practitioners identify and better support patients yet to be identified as Autistic. The authors share their best practice tips for caring for Autistic adults such as:

using strengths-based rather than deficit-based language

being open and curious about their individual experiences free of assumptions even if different than expected

allowing time and space for individuals to process information and ask and answer questions

adapt to the patient’s communication style

make accommodations for sensory processing differences (e.g., quiet places to wait)

assistance with appointment bookings and reminders to address any executive functioning differences

In addition to these recommendations, many Autistic people benefit from knowing what to expect and it is helpful for practitioners to provide an overview of any medical procedures and practices and then describe what is happening at each step in order to reduce anxiety associated with uncertainty. Being transparent about the process and reasons for choosing different treatment pathways is also recommended. When Autistic patients are undergoing a procedure, where possible, it is helpful to check in regularly and establish a means for them to signal any discomfort or need for a break. Strategies such as these can help build trust in the relationship between healthcare professionals and their Autistic patients which is so important for allaying fears and increasing the person’s capacity to stay regulated under potentially challenging circumstances.

Without wanting to overgeneralise, some Autistic people will want to share their research about what they have learned about their particular medical concerns, particularly if they have a nuanced presentation. Others may take what the practitioner says at face value and won’t necessarily think to ask any additional questions at the time. In this case, sometimes it may be beneficial to allow some processing time and revisit at a subsequent time before making any big decisions.

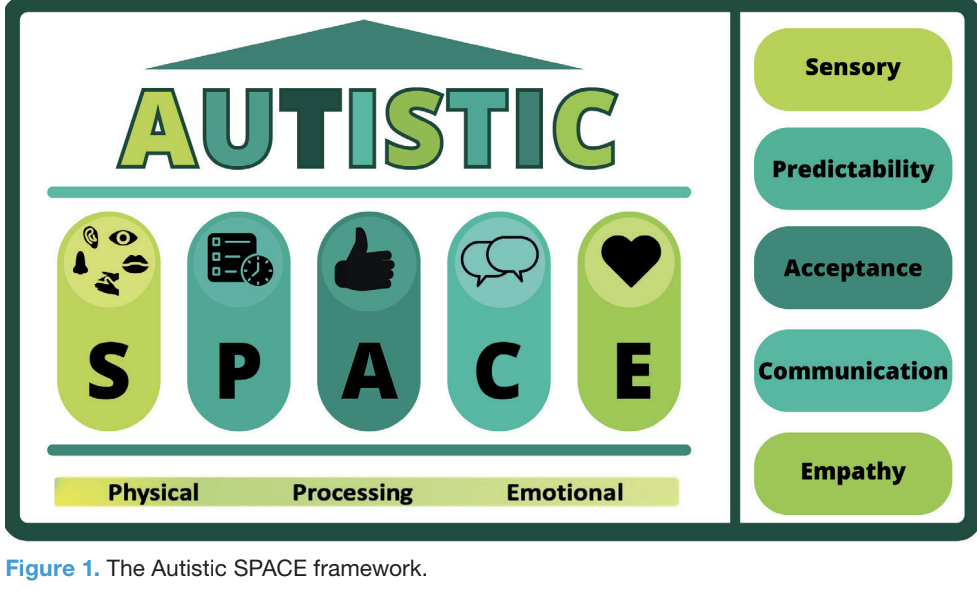

Hospital attendance or admissions can create challenges for Autistic individuals, particularly when the visit is unplanned. This can be due to meeting and needing to communicate with a variety of different and unfamiliar staff, the sensory experience (I’m thinking bright lights and hospital grade disinfectant smell), and often a lack of understanding of the nuanced individual support needs of Autistic patients. Mary Dohery and colleagues from Autistic Doctors International have developed a framework for healthcare providers to help them be mindful of accommodations and access needs of their Autistic patients.

Similar to what has been described above, this framework gives consideration to:

Adjusting sensory features of the environment

Maximising predictability to facilitate access (e.g., minimising wait-times, given information and details about the physical environment, staff involved, process and procedures, communicating and being transparent about unavoidable or unexpected changes)

Acceptance and reframing of Autistic traits from a neurodiversity affirming perspective

Increased understanding and accommodation of the variability within Autistic communication styles (both verbal and nonverbal)

Having greater empathy for the Autistic person's experience, even if it differs from our own perspective, and checking for shared understanding of treatment goals and processes.

This framework also allows for space across three other domains:

Allowing additional physical space (e.g., to decrease physical proximity to others, to support people who experience tactile defensiveness)

Allowing additional time for processing of new information or unexpected changes (e.g., in order to make important healthcare decisions)

Allowing more time for emotional processing, particularly for those who are vulnerable to overwhelm and subsequent autistic meltdown or shutdown; having a place for people to retreat to in order to process these emotional responses (e.g., they may require solitude and low sensory environment)

Another resource that can be useful for Autistic people accessing healthcare services is a “Health Passport” which can document important medical information as well as sharing important information about communication, indicators of distress and how to support regulation, sensory processing differences, indicators of pain and so on. Several examples are noted in the article from Bradshaw and colleagues listed below.

Many of these accommodations and adjustments would be of benefit to all patients accessing healthcare services as they represent a trauma informed approach to care. We hope to see continued movement towards universal implementation of neurodiversity affirming frameworks within healthcare systems to support better physical and mental health outcomes.

References

Arnold SR, Bruce G, Weise J, Mills CJ, Trollor JN, Coxon K. Barriers to healthcare for Australian autistic adults. Autism. 2023 May 10:13623613231168444. doi: 10.1177/13623613231168444. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 37161777.

Bradshaw P, Pickett C, van Driel ML, Brooker K, Urbanowicz A. Recognising, supporting and understanding Autistic adults in general practice settings. Aust J Gen Pract. 2021 Mar;50(3):126-130. doi: 10.31128/AJGP-11-20-5722. PMID: 33634275.

Doherty M, McCowan S, Shaw SC. Autistic SPACE: a novel framework for meeting the needs of autistic people in healthcare settings. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2023 Apr 2;84(4):1-9. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2023.0006. Epub 2023 Apr 17. PMID: 37127416.